“In the summer of 1976, Richard hitchhiked across the country. He was left-handed, so to avoid smearing the page with ink, he sent me a letter that had been written completely backwards like Lenardo DaVinci's notebooks. I had to hold it up to a mirror to read it.

I wrote Richard a poem in response. I answered a deep need I knew he felt for someone to affirm more than his incredible skill and talent--he needed to be loved for the totality of who he was, complete with his quirks and failures, in spite of the interference of his public persona.

My poem to Richard contained the line:

‘Though we're strangers I still love you

I love you more than your mask’”

--Rich Mullins Peace (A Communion Blessing from St. Joseph's Square)

Singing from Silence, p.54

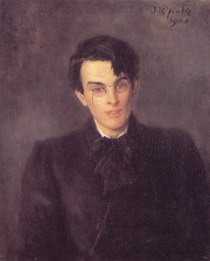

Knowing Richard as I did, I had struck on a motif that Irish poet laureate and Nobel Prize winner William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) had used throughout his literary career: the mask. Yeats’ concept of the mask seems to have been an outgrowth of his deeply held sense of personal dichotomy as an artist and an individual. As a prophetic performer with a very private personal life, duality was an experience Richard would bear in common with Yeats throughout his life.

Richard later offered a tribute to Yeats by including my line and naming his corresponding song Peace--the title of one of Yeats’ most famous poems.

The rest of the title, A Communion Blessing from St. Joseph's Square, refers specifically to a location in Dublin, Ireland—a city Yeats had inhabited, and quite possibly a place Richard visited when he shot his video for The Color Green.

The writings of Both Yeats and Mullins are derived from life experience. As a literary leader of national standing, Yeats felt drawn to evoke and breathe a national spirit into the country of his birth through his poetry. To the end of shaping the destiny of a nation, Yeats carefully defined the meanings of his metaphors and blended ancient Irish legends with his personal view of unfolding history.

Mullins, on the other hand, aspired to a transpersonal level of communication. While some of Mullin’s metaphors carry a consistent significance in his work, in his sojourn as a troubadour he encouraged variance in his listeners’ interpretations of his songs. Taking on the role of bard to the Holy King of Israel, Mullins welcomed variety in the interpretations given to his songs by his audience. He meant Americans, Irish, Quakers, Catholics, and Protestants alike to be able to find themselves in his songs.

So in his concept album, A Liturgy, a Legacy, and a Ragamuffin Band, Richard’s Quaker Irishman kisses his father’s grave in the Irish homeland and sets sail for America, where he slips into a cathedral to receive a Communion Blessing that rings all the way back from Dublin, Ireland. Here on this side of the Jordan, we Quakers don’t ordinarily practice the sacraments and Catholics may or may not hear the rocks cry out in worship of the King—unless we’ve discovered a New World transcending time, space, and limiting theologies: like the one where Mullins carries us in his songs. In an recent interview with Reed Arvin, Christopher Marchand said this about the world Richard transported his listeners to:

"A classic album makes the listener feel as if the music has always existed, but that also feels as if it came from another world altogether. A Liturgy, A Legacy, & A Ragamuffin Band is one of those albums for me."

William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats In the legend of the same name Yeats’ counterpart is a gifted songwriter, Naoise, who has captured the heart of his love Deidre through music. But since infancy, her hand has been promised to a desperately jealous king. The setting of Mullins’ song Peace may loosely allude to Deirdre. At the king’s invitation, the unsuspecting couple enters a fatal prison where a table is spread with the ruined tokens of a communion feast. Deirdre’s musicians sing: “. . . love longing is but drought for all the things that come after death.” The inspired songwriter King Solomon could hardly have said it better.

The play, like the legend, ends in tragedy. On her way to her death, Deirdre pleads with her singers to “. . . set it down in a book, that love is all we need. . .” a sentiment Mullins was later to echo.

In his tribute to W.B. Yeats, Mullins has deconstructed the Deirdre story line and retained the concept of reconciliation found in Yeats’ famous poem: Peace. By keeping the framework loose, he draws attention to Yeats’ primary motifs: mask, prison, and drought, yet allows us the latitude to identify parallels for these metaphors in our own lives.

The uplifting effect of Mullins’ Peace owes partly to its dark prison setting. Despite the dismal milieu, the songwriter finds hope in Christ, whose outstretched arms still have the “strength to reach beyond these prison bars and set us free.” Mullins offers this benediction: may His peace “rain down from heaven . . . on these souls this drought has dried.

Peace of Christ to you. . . ”

This is the eighth in a series about the upcoming book, Let the Mountains Sing. For Part Nine, click here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed