One of my favorite of his works is the Calling of Matthew. I especially love his version of the face of Christ. As always, expression is terribly important to Caravaggio.

The expression of Jesus is tender, but compelling. Revealed in a burst of light, his face is regal and dignified, yet wholly earthy and alive--even sensual. Those lips could enjoy a ripe fig, smile at the taste of wine at a wedding feast, or bless a baby with a kiss. Only an artist of Caravaggio's daring would show us Jesus with his mouth open: the Logos himself, in the act of speaking the Word. He is vocally calling Matthew to his side.

His demeanor is tranquil, not demanding or harsh. He expresses no shock at Matthew's trashy trade. Jesus knows

Matthew's whole life, from beginning to end. Jesus knows someday he'll make an artist out of Matthew: an artist who uses words. In following Christ, Matthew will witness the greatest story ever told. At last he will be called on to share that story with the world when he becomes the first writer of the Gospels.

I don't know if Caravaggio held auditions for his models. He did manage to choose one whose very facial features telegraph the action of speech: the mobile lips, the cavernous cheek, light catching the ridge covering the molars on the lower jaw, light glancing on the fine muscle rising above the moustache to the side of the nose.

The surroundings are not terribly inspiring; the room Matthew occupies is dull, mundane, and dark. He wasn't engaged in a popular occupation. Tax collectors were not known to be terribly honest in his day. There were many who thought the business of depriving his friends, relatives, and countrymen of their taxes was appropriately done in the dark. And many of us feel we are in the dark, too. Caravaggio is using the darkness to tell us that we, too can be called at any

moment. Any of us, all of us. Sinners as well as upstanding citizens from the best families--Jesus calls us all.

When I was coming up as an artist, we would never dare show our work until it was complete, and before we completed it, only to a trusted few. When we did reveal an unfinished work, the first thing we had to say was, "Well, it's not finished," a remark I compulsively recite in apology over a work in progress to this day. The idea was to have the thing the way we wanted it, and finally to unveil it--literally, to whisk off a covering at the critical moment to the awe and astonishment of onlookers.

Funny though, when we rely on that critical moment, we may give people a false impression of the creative process. This child of ours was not born in a moment, born in perfection. Art is a process, sometimes strange and painful. Just like life, just like being perfected by love.

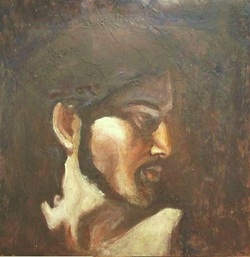

Just to demonstrate how often we are wrong more than we are right, and how we only move forward by moving back, I've been keeping records (photographs, not very well done. . .) of my progress with this work. Here they are.

Here is a blog about learning art from the masters.

Here is a copy of the head of Christ that I've been working on so I can learn from Caravaggio.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed