--Pam Richards

|

This video is the well-known interview of Rich Mullins by Artie Terry for WETN, recorded April 11, 1997. In researching my work in progress, Let the Mountains Sing, I found a few hidden gems in this interview . Since it bears on the subject of my work, the creative process of Richard Mullins, I have prepared a transcript of this interview, which I publish here. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first publication of a valid transcript of this interview in its entirety. I don't count the one that exists on youtube, which was evidently produced by a very amusing voice-to-text program, the results of which would have had Richard rolling on the floor. --Pam Richards

1 Comment

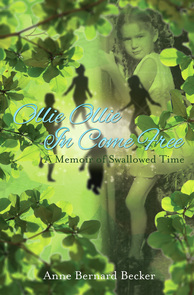

Author Anne Becker and I both live in Cincinnati, and we met through a mutual friend, Cincinnati vocal artist Paulette Meier, a previous contributor to this blog. It's been a privilege getting to know Anne as she was completing her new book. As I read Anne's book Ollie Ollie, In Come Free: A Memoir of Swallowed Time, I was honored to listen as she shared what has been perhaps the deepest journey of her heart. Her generosity with her time and expertise is reflected in the following mutual interview about sibling loss. We both had so much to say on the subject, that this article is being posted as a series. I (Pam Richards) have no qualifications as a therapist, and don't try to talk like one unless I'm prepared to be corrected by those who know better. Anne is one of those who know better. Here, Anne and I share the third part of a mutual interview about sibling loss. First, I have to apologize for the delay in posting this final interview. I have been on the road far more than usual, and unfortunately I'm not a mobile blogger. The good news is, Anne has agreed to offer a book giveaway of Ollie, Ollie In Come Free despite my delayed posting of this interview. That's grace for you! Thank you Anne. And I will offer a giveaway of Singing from Silence, too. To win the giveaway, all you have to do is comment on this three-part series before August 24, 2015. One person who comments will be selected to receive a copy of Ollie Ollie, In Come Free, and one will be selected to receive Singing from Silence. We look forward to hearing from you! * * * * * * * * * * Pam: As a young child, you exhibited an uncommon gift for creating worlds in your imagination. What were the drawbacks and gains of living so much inside your mind? Anne: I did have an extraordinarily active fantasy life. In fifth grade I read a book about Charlotte Bronte, which launched a life-long love for her. I realized recently, in reading an authoritative biography of her, that this bond was not just because of the multiple sibling deaths she experienced, or our common love for writing from an early age, but because she too had such an active fantasy life that she often felt scared it would take over. I am sure my fantasy life is what kept me functioning relatively healthily in daily life as a young girl. I could indulge in it daily, but move out of it to the "real world" of my family and friends, where the social demands to act normal, to play along, were very strong. I could not afford to act as different as I felt. But the girl I imagined in my head felt all the feelings I never dared express out loud,: sadness, abandonment, deprivation, and most of all, exquisite shame. This fantasy self was part of the identity I carried into adulthood. I found myself unable to resist the pull toward fantasy even as a young mother, even though I felt quite emotionally safe around my husband and adult friends. It is as if I had to tend to the lost self I had created as a child, and not to do so was to feel a terrible disconnection at the root of my psyche. Pam: Do you still find this gift useful as an adult? If so, how do you use it? Anne: One of the main signs of my healing in psychoanalysis in my late thirties (on which my memoir is based) was that I quit feeling a need to go into my fantasy world. I simply stopped, rather suddenly as I recall, and once I stopped, it was as if a portal closed tight. I would have no idea how to return to that world, which I no longer need. I cannot even imagine how I used to enter it! Pam: Toward your later teen years, you describe your social development (or perhaps you'd use another term) as "frozen--" unable to go back, unable to go forward. I'm intrigued. Can you describe how this affected you in your life (e.g.; by observing your behavior, what were the signs of this trait)? Anne: The primary area I am speaking of is sexual development. I felt no attraction to boys, nor did I perceive myself as a sexual being. I did not feel excited about any of the usual teen-age passions, as if they all belonged to an alien world. I dragged myself to dances, hated shopping for clothes, refused to experiment with makeup, avoided looking at myself in the mirror. Another issue for me was breaking free of my mother's very strong authority in my life. It was impossible for me to "become my own person" until I left home for college. I did not even identify any rebellious tendencies in myself, though they were there in seminal form. Pam: As I understand the concept, Freud believed that deep pain underlies the creative gifts we bring to the world. I have been told he called the process of transforming pain into creativity 'sublimation.' Does this idea resonate with you? If so, please elaborate. If not, what is your personal concept of the origin of your creativity? Anne: I actually thought Freud's idea of sublimation had to do with sexuality, rather than with pain per se. I am sure I sublimated sexual feelings as a teen-ager into my writing. Did I sublimate my pain in general into creativity while I was growing up? Possibly so. Both poetry and prose writing certainly worked as an outlet, though I would say the poetry had more of a sublimating function and the prose was more fantasy-driven. I don't believe I have used writing primarily as a tool for sublimation as an adult. I use it more as a tool for communication, to voice my truth. If it were just a means of sublimating, I would be as attracted to fiction writing and poetry as I am to memoir and personal essay. This is not the case. Telling the truth is my main need when I write. Pam: My friend was only forty-one when he died. Somehow I don't think he ever managed to move out of his imaginary worlds, as you did in your late thirties. Not only was he not in psychoanalysis, the idea of which I believe he abhorred, I think he needed those worlds for his songs, for the same reason he needed to be in touch with his pain. There was possibly also some overlap with his own practice of mysticism. Anne: You know, I have never felt there was a downside to losing my fantasy world. Perhaps Richard's was completely different from mine. Mine was very regressive psychologically -- very wrapped up in an alternative identity of a shamed child, a mythical Cinderella-in-the- Ashes. All my juvenile fiction pieces were created out of an obsession with this fantasy world, but in my mature adulthood, without the fantasies, I have been much more versatile with my creativity. And I don't experience the fantasy world that I created as at all connected with mystical experiences I have had, mostly since becoming a more integrated adult. While both involve crossing over into another realm, I have never thought about these two movements in the same breath. - very fascinating! I find myself very curious about Richard's imaginary world, and how it fed both his creativity and mysticism. I wonder if he had had a chance to integrate the hurting child self fully, how this might have transformed both his creativity and mysticism without lessening them. Pam: I guess most mystics take exception to having their worlds of vision labeled, "imaginary." They're not really imaginary like a daydream, or a fantasy. They are descriptive of a higher reality, one that the mystic knows is certainly more real than our version of the life of the senses. Our culture's current fascination with empiricism, logic and rationalism can effectively prevent us from entering those worlds. Richard consciously kept his processing, as much as he could. in line with twelfth-century thought,allowing him to access a frame of mind in which mysticism was much more the norm. I have a feeling that Richard sensed God's pain as well as his love. Pain and love were inextricably linked, in his mind. He said some things that make me believe that he cherished the kind of pain he called "passion," because it helped him understand how God experiences our rejection of him. That "pain" or "passion" fueled Richard's creative process. His songwriting was an act of transformation in itself. I don't know how or whether he fully integrated his hurting child self, but it seems to me his pain was redeemed rather than healed. This he did by sharing it with the world, touching hearts with it--as an artist does. Anne: Listening to Richard's song, "Hard to Get," I certainly hear the theme of pain, and am struck especially by the lines," I can't see how you're leading me unless you've led me here to where I'm lost enough to let myself be led." Many spiritual traditions teach that suffering brings us closer to God. It creates a powerful entry point into what Cynthia Bourgeault terms the "imaginal realm," the deeper reality you speak of that underlies the life of the senses. The "way of the Cross" is particularly core to Christian spirituality. I know I have experienced its power in my own life. And I've worried (like Richard?) that being too contented, too integrated, too anxiety-free might keep me from seeking God's love -- but no worry: life events inevitably have a way of taking us deeper into the Passion! I think It's a matter of cultivating a spiritual openness, a heart that is truly awake, an energy that is attuned to the divine, "in good times and in bad." Is this easier to access the imaginal realm when emotional blocks have been healed? For me, yes, but Richard had his own path, his own way of manifesting God on this earth. Pam: I agree there isn't much point chasing after suffering. As Richard observed, "bound to come some trouble in your life." Some people pity Richard when they hear Hard to Get, but there is no reason to single him out as the only one who ever felt this way. This song is Richard's "dark night of the soul," as experienced by many mystics who find their path leads to a temporary disconnection of their experience of God's presence. There comes a time when we walk those dark roads by faith, not by the spiritual "sight" our earlier experience has accustomed us to. It is a test of our faithfulness to God, in continuing to seek him with or without the reward of sensing his presence. It is considered by many to be a sign of spiritual awareness to be called to walk this path. Mystics like Bourgeault would tend to agree that we all have our own journey, and this, it seems, was Richard's. Your healing may have come through psychoanalysis, mine has come through seeing the love of God through a human being; Richard's journey included the way of the cross. In truth, shortly after he wrote this song, I believe Richard was transferred from the pain of absence into the joy of the presence of God. That is the true reunion we all long for; all the others we mourn are, in a sense, metaphors in our lives for our longing for God.  Anne Becker, Author Anne Bernard Becker facilitates workshops exploring the effects of intergenerational trauma on families, and is also an ordained wedding officiant. Her recently published book, Ollie Ollie In Come Free: A Memoir of Swalllowed Time, explores the impact of her older siblings' deaths on her childhood and growth into adulthood. It is based on insights gained in psychoanalysis in the 1980's and 1990's. Besides writing, Anne loves choral singing and exploring history, psychology, and spirituality. She enjoys walks with her dog, and daily life with her husband of thirty-four years, Gerry. They have three adult children living in widely scattered places. She has worked part-time since 2001 as a learning coordinator at a private learning center. Since 1985, she and Gerry have belonged to New Jerusalem, an alternative Catholic community in Cincinnati.  Author Anne Becker and I both live in Cincinnati, and we met through a mutual friend, Cincinnati vocal artist Paulette Meier, a previous contributor to this blog. It's been a privilege getting to know Anne as she was completing her new book. As I read Anne's book Ollie Ollie, In Come Free: A Memoir of Swallowed Time, I was honored to listen as she shared what has been perhaps the deepest journey of her heart. Her generosity with her time and expertise is reflected in the following mutual interview about sibling loss. We both had so much to say on the subject, that this article is being posted as a series. I (Pam Richards) have no qualifications as a therapist, and don't try to talk like one unless I'm prepared to be corrected by those who know better. Anne is one of those who know better. Here, Anne and I share the second part of a mutual interview about sibling loss. Anne: Pam, I have been wondering why you chose to write a book about your bond with Rich Mullins at this particular time in your life. Obviously your love for one another had long been a privately cherished experience in your life, and it stayed that way for many years. What changed in your inner life or outer circumstances that led you to write this book? Pam: I felt deep guilt because of not being able to speak to Richard in the last years of his life, which made it very difficult for me even to think of him until more than a decade after his death. Overall, this relationship has been the most puzzling event of my life. After writing vignettes of my memories, I had a deep healing experience which allowed me to see the relationship through different eyes. To clarify, I would say that much of my grief was healed very rapidly before I completed writing the book, not after. In turn, that shift prompted me to write the book, Singing from Silence. In fact, I'd never have written it if I hadn't had such an astonishing healing experience. I wouldn't have been able to delve as deeply as I did--it would have hurt too much. Anne, what similarities did you find between Singing from Silence and Ollie, Ollie In Come Free? I found quite a few. Anne: The most obvious similarity is in the love and longing we both have for a brother--if I can call Rich your brother--who is no longer available to us. Our grief was frozen and unavailable to us for many years, mired in confusion, until we could honestly face it. Our memoirs serve to bring closure to the years of numbed-out pining, to mourn consciously at last, and to honor the beauty of the bond through telling the story. Pam: Sometimes I did see Richard as a brother, sometimes a son, sometimes a father. Anything but a boyfriend! That's another book. On a more subtle level, perhaps, there are some similarities between your life and mine because I had twin brothers who died the morning after they were born. It was before I was born, and I don't go into it much in the book; I just state the facts, but it's an event that affected my mother profoundly. If my mother was ever carefree and nurturing, I lost that part of her along with my brothers. Anne: Yes, this is an interesting similarity in our life stories. It is so difficult to know how responsive and nurturing our parents might have been without these losses--it is possible that they were already somewhat shut down emotionally--yet I can't help but believe their ability to parent was profoundly impacted, especially since they were not encouraged to mourn. Pam: Tolstoy wrote, "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." How do you feel about this statement? Do you think your book illustrates this point? Anne: I wonder if Tolstoy somehow had it wrong. I don't know if unhappy families exist. Unhappy individuals within families, yes. But I think families have a way of assuring that they are "happy" as a system. I am a practitioner of Systemic Constellation work. What I see is that families develop a solid defense system that keeps them going from generation to generation without any desire to be transformed, to become "happier." No matter how unhappy the family appears, the members are sure this is the right way to be. What causes individuals to become unhappy is when they opt out of the family feeling of well-being. I don't know how this happens to others, but with me it began at a very early age. I struggled with a terrible loyalty to those siblings who had died, a sense that it was wrong to just move on, as the family ethic somehow dictated we must do, for survival's sake. Did others within the family go on to enjoy more happiness? Some did, others not, for their own reasons. But the family as a whole remained confident, cocky, even, about its happiness, its ability to be victorious over all forces that might undermine it. The family is much bigger than the individuals within it, who will find themselves isolated if they dare to question the family's happiness. To be continued. . .  Anne Becker, Author Anne Bernard Becker facilitates workshops exploring the effects of intergenerational trauma on families, and is also an ordained wedding officiant. Her recently published book, Ollie Ollie In Come Free: A Memoir of Swalllowed Time, explores the impact of her older siblings' deaths on her childhood and growth into adulthood. It is based on insights gained in psychoanalysis in the 1980's and 1990's. Besides writing, Anne loves choral singing and exploring history, psychology, and spirituality. She enjoys walks with her dog, and daily life with her husband of thirty-four years, Gerry. They have three adult children living in widely scattered places. She has worked part-time since 2001 as a learning coordinator at a private learning center. Since 1985, she and Gerry have belonged to New Jerusalem, an alternative Catholic community in Cincinnati.  Author Anne Becker and I both live in Cincinnati, and we met through a mutual friend, Cincinnati vocal artist Paulette Meier, a previous contributor to this blog. It's been a privilege getting to know Anne as she was completing her new book. As I read Anne's book Ollie Ollie, In Come Free: A Memoir of Swallowed Time, I was honored to listen as she shared what has been perhaps the deepest journey of her heart. Her generosity with her time and expertise is reflected in the following mutual interview about sibling loss. We both had so much to say on the subject, that this article is being posted as a series. I (Pam Richards) have no qualifications as a therapist, and don't try to talk like one unless I'm prepared to be corrected by those who know better. Anne is one of those who know better. Pam: Anne, what's the spark that engendered your creative work, Ollie Ollie, In Come Free? Getting to the root of it, is there some incident in your life, some sine qua non "without which" your book would not have been written? Anne: I had been in psychoanalysis for six years when I began to jot down the vignettes from my childhood that would later be formed into my memoir. What I had uncovered in psychoanalysis through those years was my frozen grief over my older brother and sisters' deaths when I was a small child, and how it impacted every aspect of my being. Now those experiences began to pour out of me in written form. I had immediate access to a flood of memories and feelings, and even to the narrative voice of the young girl I had once been. I shared my stories in a women's writing group where I felt warm, safe and received, and the effect was cathartic because it seemed, in fantasy, to fulfill my deepest lifetime yearning to be heard and understood by my family. In the family I had never been able to reveal my sadness, my longings, terror of death, shame or survivor guilt. I had often felt lonely and alienated, though I had never revealed these feelings because they would be dismissed and ridiculed. After a few months this thought came to me: "If my mother and sisters can read these stories as they come directly from my guileless child self, unfiltered, fresh and raw like an eye-witness account, they will finally know how I have suffered. " The thought was deliciously consoling to me. It took twenty years for my book to come to fruition. During that time, right up through publication, my focus was on revealing my truth to my family, and thus giving my child self a voice for the first time. If I was to share the book with the public, as I also longed to do, it was in large part so others outside the family could bear witness and validate my experiences. Without psychoanalysis, without Women Writing for (a) Change, I would have never been able to write such an intimate memoir. It took the juxtaposition of both experiences to give me both the insight and the courage to share my experiences in this way. Pam: Anne, I grew up with a heavy set of expectations, following the loss of my siblings and several miscarriages my mother endured. I was a "last chance" baby, born when my mother was forty. As a result of sibling loss, I felt like the "miracle baby." I never felt I could live up to the expectations of others. Did you have a similar experience, and if so, how do you think it affected you? Anne: This is a tough question to address. On the surface,I did not have a special place in the family that would have led to high expectations. In fact I was often told, growing up, that my arrival was traumatic for my mother because it occurred at the same time my oldest sister Mary-Louise started kindergarten. Suddenly the cozy little nest my mother treasured exploded with a fourth kid, a colicky one at that, while she had to turn her oldest over to alien authorities every morning. With my birth, she grieved her losses. On the other hand I believe I did become a replacement child for Mary-Louise after she died. I was certainly not conscious of this while growing up, but my mother alluded to it decades later, and as I thought about it, it matched my experience. I had many of her personality traits, so the identification would have been easy. Also, my mother started a private school for me, and she did imply later that this felt like a way to love Mary-Louise, for whom she could do nothing. I was put up on a pedestal as time passed; I was always being told by adults how bright I was. Some of my sense of specialness may have been of my own making, as a defense against my loneliness -- I worked really hard at being super-good. I became a book-worm and a pianist. High expectations were so internalized, the need to shine so intense, that I have never experienced them as coming from outside of me. If it weren't for the remarks my mother made to me in 1990, it would never have occurred to me that there was any identification with my dead sister. Such things are so subliminal, so unconscious on everyone's part that they are hard to know for sure. Did I feel special, for one reason or another? Absolutely. Pam, I am interested in how the bond between you and Richard might have grown out of your shared sense of specialness. You were both following the beat of a different drummer. Pam: Richard knew he was a prodigy, certainly by the time we met. It's a specialness that can set someone apart from his peers. For instance, he devoted more time to playing classical piano growing up, and less to sports. So he was more isolated when he was young than most. When he had an audience, though, he could let his gift shine. He knew this even before junior high school, when he began accompanying a youth choir. As a performer, he was very natural. Socially, however, his experiences were limited as he developed his gift. As for me, I don't remember a time when I couldn't read, so a lot was expected of me academically--even though my math skills lag far behind the verbal skills. Advanced reading was a skill my peers did not appreciate, so it wasn't easy making friends. I also had a difficult time at home, so I spent most of my childhood entranced in a book. I only started making friends when I was a senior in high school, learning everything I could about art, creating art, and creativity. So when we both met as freshmen in 1974, Richard and I both lived in our inner worlds a lot. Richard's world of songwriting and mine of visual imagination gave both of us a point of intersection. Our relationship was so intense it was a downright scary, so our shared world of inner images acted perhaps as a buffer, allowing us to interact at a safe distance--yet at the same time forming a deep bond between us. I'm no exception there--Richard seemed intent on bonding with virtually anyone and everyone he met. Many people relate to others in a variety of ways: through competition, through teaching/learning, through varying patterns of courting relationships. Richard seemed especially adapted to creating a bond by mirroring the person he was with. Here's a link to an NPR podcast someone recently shared with me about quantum entanglement applied to human interactions. The type of empathy they're talking about is extreme, but I can catch a glimpse of Richard in it. http://www.npr.org/2015/01/30/382453493/mirror-touch By the time Richard went on to a career as a performer, he had enough ability to guide the emotional experiences of his audience that he could readily face a crowd without fear of being overwhelmed. To be continued. . . Anne Becker, Author Anne Bernard Becker facilitates workshops exploring the effects of intergenerational trauma on families, and is also an ordained wedding officiant. Her recently published book, Ollie Ollie In Come Free: A Memoir of Swalllowed Time, explores the impact of her older siblings' deaths on her childhood and growth into adulthood. It is based on insights gained in psychoanalysis in the 1980's and 1990's. Besides writing, Anne loves choral singing and exploring history, psychology, and spirituality. She enjoys walks with her dog, and daily life with her husband of thirty-four years, Gerry. They have three adult children living in widely scattered places. She has worked part-time since 2001 as a learning coordinator at a private learning center. Since 1985, she and Gerry have belonged to New Jerusalem, an alternative Catholic community in Cincinnati.

I've observed in radio interviews that Rich Mullins was fairly consistently asked to explain the personal meaning behind his most recently released songs. His responses were extremely guarded. When asked why he'd written a song, or what it meant to him personally, he was more likely to describe the immediate set of circumstances that led up to the songwriting event. His personal reasons for writing a given song remained opaque. Here's a paraphrase of a radio interview: Interviewer: "What does the song "Maker of Noses" mean to you?" RWM: (offers a long discussion of the events leading up to the writing of the song. His description touches on the need for the song, the pressures surrounding the writing of the song, the physical setting of writing the song, and who he co-wrote it with--without surfacing a single personal association with the song.) A fan responded to the interview along the lines of, "This is great! I always wondered why he wrote 'Maker of Noses!'" I don't object to anyone wanting to hear the events that led up to Richard writing any of his songs. I would like to point out, though, that if we think Richard answered that question, we've all bought a song--and a dance. That is a statement of admiration, not hostility. I love Richard's understanding of how to use his talents. The dance move which allows him to sidestep that question is not executed as an evasion: it is a gift to his audience. Richard valued the fact that his songs spun out multiple meanings for his listeners. His silence about the personal significance of his songs preserved for his audience members the gift of making their own associations. Far from being deceptive, Richard was doing what a good Quaker elder would do--throwing us back on our own Inner Teacher to unfold the truths these songs were meant to show us. I believe the artist is correct to deflect attention from the personal to the universal. This is part of what William Butler Yeats meant when he described the performer's Mask. This is not the mask of self-deception and separation from God; rather, this Mask is a tool in the hands of the artist to bring the members of the audience into contact with their own inner dialogue. Richard used it wisely, and he used it well. Yet its use comes at a sacrifice. The performer knows that the Mask means that very few people know who he really is. During his lifetime, the Mask will make him a lonelier man, but it will multiply his gift to his audience. Now that Richard is no longer here with us, we each have the option of deciding for ourselves how long we need to keep him behind the performer's mask. Would he want us to know who he was? During his lifetime, his privacy was quite important to him. But his privacy is of no use to him now that his life on earth has ended. Meanwhile, we do know he deeply regretted being placed on a pedestal by his audience. Some among his fans seem to be drawn to the Rich Mullins phenomenon, yet they do not appear to be ready to deal with the person himself. "I don't want to know about his personal life," some say. I understand the hesitation. What if the man behind the mask isn't simply "just like us?" What if he is more challenging to love, or more wounded than we thought? What if he is even more gifted than we had imagined? What if we found him beyond explanation or comprehension? What category would we put the wild man Rich Mullins in to keep ourselves safe from his effect on us? What if his God was too big for the box we want to build for him? To see beyond the mask is to begin to take greater steps in faith. Not everyone is ready for the journey at the same time, and no one needs to be pushed. It's something like the moment when we learn our parents were human, that they made some of the same mistakes they warned us not to make. It's shocking yet comforting to realize that even those we thought were perfect have faced their moments of trial, loss, repentance, grace. In fact, we can begin to experience compassion for them, which this is the true gateway to the Kingdom of Heaven within us. Anyone ready for an inside look at the life and creative journey of the early Rich Mullins? "No, leave the mask there," some will say. To which I'd respond, "Which mask?" We've had the CCM cleaned-up mask, the Arrow Pointing to Heaven devotional mask, now the fictional Ragamuffin mask. Sadly, the more masks we place to obscure Richard's actual experiences, the more of his unique identity we bury; the more we project our own issues onto him, the less we can learn from his life. Scriptures show us an entirely different approach to humanity's stumbling. Not even one of the people we meet in these pages is masked like a performer or kept on a pedestal like a celebrity. Adam falls, Noah drinks, Abraham panders, Jacob deceives, Moses both blasphemes and murders, King David, to his heartfelt remorse, murders and commits adultery, Jonah bolts, Thomas doubts, Peter denies, Paul, aka Saul, persecutes the early church. . . and only One stands out as truly righteous. Why does Scripture force us to face the humanity of these outstanding figures of faith? It seems there are lessons to be learned from human weakness and failure. Maybe it's because we are so drawn to find what we have in common with great people. Perhaps when we find frailty in the great, we can admit to it in ourselves. All these lessons remain invisible to us, however, while we let the mask hide them. Every year, there are fewer left this side of the Jordan who remember Richard for who he was behind the mask. The next twenty years or so, give or take a decade, is the time remaining for us to pass on what we know. I may be one of the first to write about Richard's hidden years not because I'm more brave or insightful, but because I feel time passing more quickly. Since even before my stroke, I've had significant health concerns. I don't feel I have the luxury of waiting until a great number of people are interested or ready to seek it out, so I know my writing is not likely to make me popular. My own piece is limited, because like everyone, I'm constrained by time and space. I'm not omniscient; why try to explain or describe what happened between Richard and others when I was not present? I believe it takes a lifetime to learn a life, and so with gratitude I still learn more from Richard all the time. I know there are others who also have important contributions to make to our understanding of Richard Mullins, and therefore of ourselves. I have the honor of including some in-depth material from one of the musicians who was involved with Richard's creative work during his formative years in Let the Mountains Sing. We can hope to hear more from him and others like him as time goes on. To those followers Not Ready to Look Behind the Mask: I understand that this task must be undertaken in faith, and no one can ask you to take it up until you are ready. I respectfully suggest you delay reading non-fictional material about Richard Mullins' hidden years like Singing from Silence and Let the Mountains Sing as long as the Holy Spirit allows. This is the first in a nine-part series on the upcoming book, Let the Mountains Sing. For Part Two, click here. Here's an update on the book about Rich Mullins I'm currently writing, Let the Mountains Sing. . . This is the second in a series about the upcoming book, Let the Mountains Sing. Click here for Part Two.

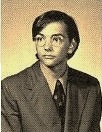

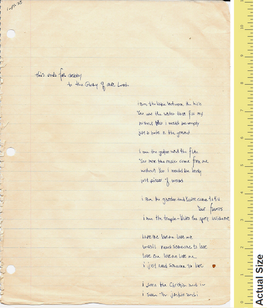

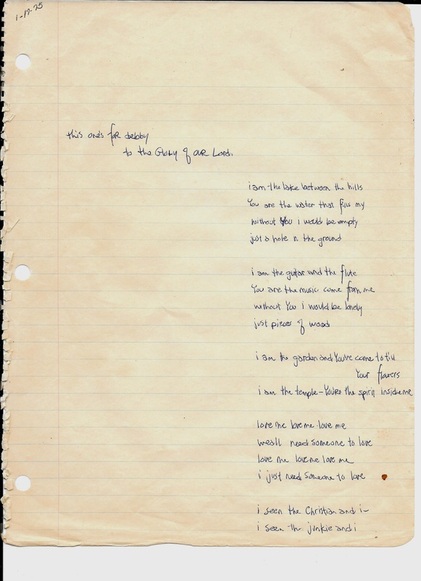

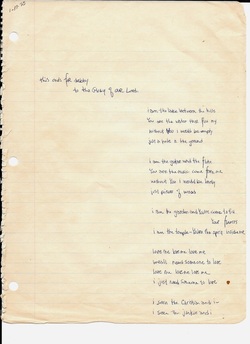

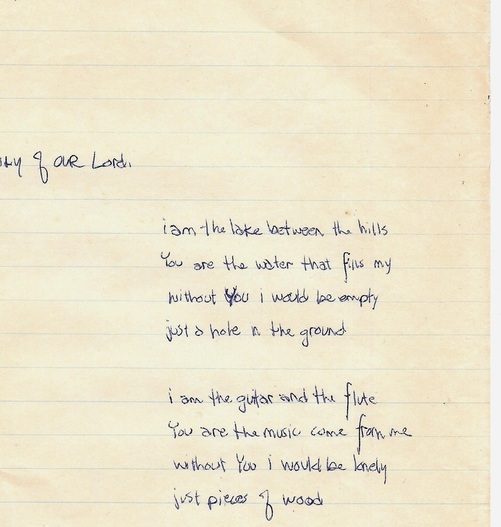

For Part Three, Forty Years Have Passed, click here. For Part Four, Classical Mullins, click here For Part Five, Here be Dragons, click here For Part Six, Hearing God's Voice, Doing His Work, click here For Part Seven, Rich Mullins Between the Lines and Beyond the Footlights, click here For Part Eight, Ragamuffin Legacy Part Four: Both are Bards, click here For Part Nine, Bringing Stained Glass to Life, click here For Part One, A Song, a Dance. . . and a Mask, click here  Here are a few excerpts from a handwriting analysis by Sandra Fisher of Graphic Insight. His handwriting reveals that Richard could be quite private, even to those who were supposed to know him best. A longer version of this professional analysis is posted here: ". . . It seems as if he had his antennae out in all directions. He had insight into many things that gave him an almost uncanny perception and understanding of the world around him but it also made him vulnerable. . . " ". . .In Richard’s case, he put up an effective barrier around himself that may have been difficult to penetrate. This was not a noticeable barrier but it was there nevertheless and he must have thought that it shielded him from the arrows of life which he perceived to be a threat to his equilibrium. . ." " . . . He coped with some of his anxieties by keeping an emotional distance from people. It made him feel safer to feel that he was not allowing them to encroach on his inner world. . . " ". . . Richard was no weakling. He was self-reliant and independent. There was even something slightly rebellious about him. He did his own thing regardless of any criticism. . . " ". . . As someone who felt he had a mission to fulfill he found it easier to open himself up to the world at large rather than to his family and friends. And so he gave much of himself to the world but kept his closer relationships at arm’s length. . . "  Handwriting analysis can be so accurate, it's almost frightening. But it is able to show only our natural inclinations, strengths, and challenges--not the astonishing things God is able to accomplish when he shines through our weaknesses. I find it interesting to use handwriting analysis as a filter to show the contrast between Richard's natural human personality and what he let God do with his servant's heart, which is usually most apparent in the videos of his performances. Yes, Jason Boyett, his handwriting suggests he did dislike the limelight. But his sense of responsibility to use his gifts was greater than his retiring nature. You can probably detect that this analysis was done by someone who knew Richard pretty well. For instance, someone who knew Richard's favorite poet at the time, and his interest in the Grail legends. The analyst is me--I began studying handwriting analysis as a child. The upshot of this particular analysis is--Richard's major means of revealing his personal feelings was through his songs. They were perhaps the only outlet he had for his deepest emotions. If you wanted to know how or what Richard was feeling, you let him take you to the nearest piano. The heart he showed in his songs was the true one: he was no hypocrite, no superficial manipulator of emotions just because he could. The things he couldn't say to your face were the things he would sing. He was nineteen years old when he wrote this sample, and younger when he wrote the song. His search for the love of God had begun in earnest long before he ever heard of Brennan Manning. Of course, an analysis is only as good as the analyst. I submitted this sample and the analysis I produced to a professional, Sandra Fisher, and her remarks follow: "I found your analysis of the situation very detailed and insightful. How very complex it is. And what a very complex man he must have been." I will be posting excerpts from Sandra's own analysis here on my blog in the near future.  What was the real Rich Mullins really like? Turns out Jason Boyett's perception of Richard's reluctance to take his place in the limelight is supported by handwriting analysis! This is a brief analysis of a handwriting sample produced by Richard Wayne Mullins in January 1975 in response to a personal friend's request for one of his song lyrics. Debbie Blackwell Buckley, to whom this example was inscribed, has kindly given her permission to post it here. She witnessed him write these pages and affirms it is his own natural handwriting. The pressure on the page is light; it does not leave a mark on the reverse side of the page. The left margin of the first page is enormous, indicating a devotion to artistic form and a high degree of ambition. The entire song is presented on precisely two pages, not a line more or less. This demonstrates keen mental organization and intellectual process. The second page presents a substantially more moderate left margin, revealing that the writer has recalled and accommodated the somewhat longer lines in the second half of the lyric. Memory and planning are notable strengths. The writer's favorite poet at the time of this writing was E.E. Cummings. Choosing to emulate Cummings' style, Mullins has left out out all punctuation and capitalization, with one exception. The lack of punctuation lends a transcendent quality to the written lyric, as though leaving the reader to envision alternate phrasings: an invitation to interpretation. Like Cummings', Mullins' personal pronoun "I" is formed as a lowercase letter. While this may indicate humility or a tendency to identify with everyman, it may also hint at a diffusion of personal accountability, and perhaps an alienation from family ties. His signature shows the same lack of capitalization. These conventions characterized E.E. Cummings' work, but Mullins deliberately chose to adopt them at this phase of his life, demonstrating his personal affinity with these poetic forms.* *Later in his life, Mullins re-adopted the use of standard punctuation and capitalization. This intermittent phase seems to have been fairly short-lived, possibly starting before he began college and ending sometime in his college years. Mullins told me that he was placed in the lowest section of his Freshman English class, although I found it difficult to believe. If he was leaving out capitals and punctuation, this may account for his low placement. Mullins himself did not seem to care, showing no hurt pride about his placement. He was just as content with easier assignments, which gave him more time for music. The writer uses the capital letter form only when referring to God. But it is noteworthy that his second reference to God is begun by forming a lowercase "y," overwritten with an uppercase "Y." This alternation suggests that like many great poets, the writer superimposes a divine relationship on a human one--or uses one to represent the other. The shape of this uppercase Y is, as far as the analyst can tell, unprecedented in handwriting literature. A remarkable degree of creativity is displayed in this letter, shaped like a goblet or a chalice—or perhaps like the Grail.** **The writer had a fascination with the Grail legends when he wrote this sample. There is a fluidity to the writing as it appears on the page, an effortless expression of creativity and rhythm. The lowercase "i"s are carefully dotted, falling neither to the left or right of the "i" stem. This is an indication of precise attention to detail, active memory and personal loyalty. The writer's signature is the same size as the rest of his writing and contains no capital letters, demonstrating the consistent nature of his personal humility. The writing shows a tendency to stray below then line, then revert to it. Together with his slightly left-leaning, alternated with a slightly right-leaning slant, it appears the writer is moody, prone to depression, and at times acts out a dual nature, an almost simultaneous push/pull in relationships. The miniscule size of the writing, the close spacing of letters within words, and the greater distances between words suggest the writer is capable of an intense degree of concentration yet remains highly private about his inner life. It is more than a need for space, indicated by the large spaces between words; more than a difficulty letting people in, shown by the tight spacing of the letters within words. The tiny writing shows his extreme introversion and a brilliant intellect capable of handling an overwhelming amount of detail. Einstein and Da Vinci both had small handwriting. This writing is approximately 3/4 the size of Albert Einstein's--very small indeed. The light pressure on the page indicates a highly sensitive nature. All these factors together suggest his feelings tend to be pent up; when he does express them, he may lose his temper abruptly. The precise closures of his vowels indicate integrity. He will be honest, on his own terms. However, he is fully capable of keeping a confidence--which means he won't tell everything he knows. The man who wrote this sample shows indications of being an extremely lonely individual who is reluctant to communicate how he really feels. What motivates this writer? Not every handwriting sample reveals so clearly the writer’s personal vortex. This writer appears to be obsessive. What is the focal point of his obsession? This would be demonstrated by the letters of the words he overwrites: the y in "you" and "You." His concept of a relationship with God is superimposed on a human relationship. There is inherently nothing wrong or evil or sinful about this, as the Song of Songs demonstrates. This writer is obsessed with the idea of such a relationship.*** The focal point of his obsession, it is the vortex on which his life spins, because personal intimacy is his Achilles heel: the weakest link in his personal inventory. ***Tellingly, the writer believed obsession to be a characteristic of divine love. For some larger views of this sample, click here For some notes on this analysis, click here This is the seventh in a series of posts about the upcoming book, Let the Mountains Sing. The eighth is here.  We all know who Rich Mullins was when he was on stage: vastly entertaining, gregarious, a bit of a showman. Yet along with his bright wit he spoke from a depth which resonated of something more than glib performance. Clearly, he was a man of many sides. Performing is a profession. It is difficult to distinguish when performers are being genuine and when they are being--well, good at their jobs. What traits did Richard consistently display when he was off stage? What motivated him? What made him tick? What was the real Richard Wayne Mullins really like? The answers provided by graphology, the study of handwriting, may help clarify some of the mysteries surrounding a man who had so much to offer, yet displayed such a changeable nature. This sample of Richard's handwriting was kindly volunteered by a good friend of Richard's since his freshman year at Bible College, Debbie Blackwell Buckley. Debbie and I occupied "next-door" rooms on the third floor of Alumni Hall that year. One day in January 1975, she approached Richard and asked him to write out the lyrics of her favorite of his songs at the time, one called "Lake Between the Hills." Although Richard probably performed this song a little differently every time he sang it, he sat down and wrote these lyrics out for Debbie on the spot. In my next blog entry, I'll be posting an analysis which will describe the traits of the man who wrote this sample. I'll show both pages of this sample and give you a few close-up views of his writing, too. Here's one close-up: |

Pam RichardsGod help me, I'm an artist. Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

Blogroll

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed